Through the Lens of Those We Love

Uplifting Oral Histories and Finding Common Threads

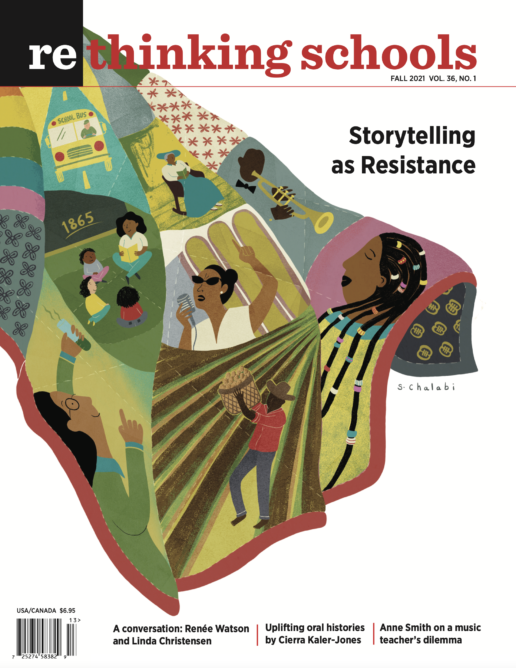

Illustrator: Howard Barry

In some ways, schools have historically been sites of forgetting, where whitewashed, sanitized versions of history that privilege the dominant narrative are uplifted, and rich legacies of resistance and collective struggle are erased. For example, the young people I learn alongside and I learned about Tulsa’s Greenwood District, otherwise known as Black Wall Street, together. We were frustrated that we never learned about the bustling, prosperous area of growth and culture, only about how a mob of white supremacists perpetrated devastation and violence against the community. Mackenzie, a talented photographer and coder, said, “I feel like it was erased from textbooks because it was something good Black people did. Textbooks should explain that Black history is full of success.” Rather, the narrative was focused on the community’s demise at the hands of white rage, without also telling the stories of Black community members and their creativity, ingenuity, and inventiveness.

By encouraging young people to not only be curious about the histories that live within their own lineage, but to bring that knowledge to the classroom as well, we can create space for remembering. The act of remembering taps into what students know from their communities, elders, and ancestors. It reminds us of what we know that has been passed down to us, despite how school policies and curricula may suppress the enactment of that knowledge.

History is not only around us, but also within us. It is not something that just takes place in textbooks or “out there,” but rather something we make each day. History is etched into the fabric of our loved ones’ beings and we can breathe life into the stories that make up the essence of who we are individually and collectively by exploring our stories, communicating them, and passing them on.

During the summer of 2020, I developed a virtual arts-based program called Black Girls S.O.A.R. (Scholarship, Organizing, Arts, and Resistance) alongside eight high school-aged Black girls, who I call my co-researchers. I use this term because language is an important tool in beginning to disrupt beliefs about who holds knowledge and who has the power to shape knowledge. As educators, we are constantly learning and growing alongside young people.

I created this program because as a dance educator, young people were coming to the after-school dance space with thoughtful questions and reflections about their educational experiences. I realized in my first two years of teaching that when I greeted each student, asking them about their day and what they learned in school, they often replied with what they did not learn. As the dance seasons went on, I recognized a pattern in many of the questions they asked me. They inquired with requests such as “Can we learn about Africa? I haven’t learned anything about Africa at school.” “Can we talk about racism? My teacher told me I couldn’t wear my hair in braids and it’s not right.” “Can we talk about current events? There’s so many things going on in the world and I want to do something to make change.” The young people I learned with were not only curious about the education they deserve, but actively asked for it as well. As I adapted my dance lessons to respond to their questions, I realized that I, too, was denied learning about my ancestors and my own history. I started weaving Black history lessons and conversations about current events into the dance curriculum, and these lessons ultimately became the framework for Black Girls S.O.A.R. Our collective explored and discovered what could become possible when we viewed the history that lives in our lineage.

The Black Girls S.O.A.R. co-researchers attended school in both the Washington, D.C., metro area and Columbia, South Carolina. They joined the program after expressing their interest from a flier and promotional materials about bringing together a research group dedicated to centering Black girls’ knowledge and expertise. Although some came into the program as friends, as a collective many of us had met only virtually as part of Black Girls S.O.A.R.

We met for five two-hour sessions on Zoom during the summer months. I started the program with individual pre-interviews, asking them each what they wanted to have conversations about. I followed up by taking the themes, such as hair, identity, and history, to pull together lesson ideas. The curriculum was iterative, in that as the sessions went on, co-researchers would bring their interests to the group and we adapted the curriculum to their interests. The activities and prompts of each session were informed by the conversations we had in previous sessions.

Together, we researched and learned about Black Feminist Theory, Black history, Afrofuturism, leadership, activism, and community organizing through a healing-centered lens. We used art, such as dance, visual art, animation, and poetry, to process and reflect on what we learned and discussed. Throughout the program, we practiced qualitative coding and analyzing data. As part of data collection, we gathered oral history testimonies from our loved ones. We also recorded our conversations throughout the program and viewed the transcripts of our own words to see our perspectives as commensurate with research. It was important to me to engage in data collection and analysis because what is often considered to be “data” or “evidence” has been a form of intellectual policing, where the rules around what is regarded as knowledge have been socially constructed to privilege the values of white supremacy, such as objectivity. We reclaimed the meaning of data by centering ourselves and our loved ones in the narrative. To culminate the program, we turned themes from the oral histories and other data we collected into artwork that we presented to loved ones in a community arts showcase.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, my co-researchers and I recognized that the moment we are living in is history that will be catalogued for centuries to come. We carefully watched the news, debunked myths we saw on social media, and lamented how history textbooks might illustrate the compounding factors of a pandemic, continued racial injustice and subsequent rebellion, and an ongoing climate crisis. We didn’t want our experiences to be forgotten in the textbook like the successes of Black Wall Street. In response, we picked up our literal and figurative pens to ensure that our stories, and our loved ones’ stories, would be told accurately and truthfully.

Coming Up with Questions

Before we began our conversation about oral histories, I opened up a dialogue to learn more about what students had learned about Black history, particularly in their experiences at school. I asked, “What have you learned about Black history?” After a pause, they cited the only topics they covered at school were enslavement, Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and Martin Luther King Jr. Alia, a brilliant singer and tennis player, went on to say, “History is reflected by those who write it,” namely from the perspective of white men. Briana and Mackenzie added the clapping emoji as a reaction on Zoom, while Jessie, Camille, and Lisa wrote exclamation points and words of affirmation in the chat. The co-researchers were excited about the idea that although history was often written about them, they could rewrite history to elevate their experiences.

Camille brought us to a pause: “Wait, there are so many stories we can tell!” They could use their art to tell stories that had been left out of the curriculum. History could be reflected by them.

To collect oral histories, we started with the question “If we were to rewrite the history textbooks, what stories would we want to tell?” This provided a foundation for collectively expressing what we felt is missing from textbooks.

Then I said, “Think about someone you love and makes you feel loved, someone you admire, someone whose story you want to highlight in history. Loved ones can mean something different to all of us.” I went on to share with them my reasoning for using this language: “I specifically chose the framing of loved ones, rather than family members, to be mindful of the many ways families look and feel to individuals.” This also honors the principle of uplifting Black villages by disrupting Western definitions of families to extend how we love and care for one another beyond nuclear constructions. I did not ask them to share who they would interview in the moment, as I wanted them to have reflective and creative space to process who they would want to learn from.

After five minutes for sacred pause and reflection, I opened up space to think about what questions we would want to ask our loved ones. We created a collective interview protocol, a collaborative Google document that had all of the questions we brainstormed together. The first part of the protocol was a script that outlined how we would introduce our questions and ask loved ones for consent. For example, ours read, “My co-researchers and I are conducting a research project where we are collecting oral histories to rewrite history textbooks with our loved ones’ stories. I am interested in interviewing you and learning more about your story. Do you feel comfortable with me asking you some questions to learn from you?”

To begin to think about specific questions, I asked, “What questions would you want to ask your loved ones? What do you want to know about their lives and their perspectives? Are there any moments in history they could talk about from their experience?” I emphasized the importance of using who, what, where, when, and why questions because they are open-ended and would encourage more descriptive answers than closed questions or leading questions.

The goal was to have the loved one take us through moments in time, so we could detail history from their perspective. Some co-researchers typed their questions in the document, others shared out loud. We supported one another as we worked through the questions together: “How does this sound? How would you rephrase this? Is this question clear?” Some of the questions were:

What do you remember about your childhood?

Where did you grow up? What was it like?

Who was your mentor? What were

(or are) they like? Who inspired you to be who you are now?

What are your outlets for expression?

What causes are you passionate about?

What do you remember from [insert moment in history]?

What’s a choice you had to make that affected your community?

If you were going to be in a textbook, what would you say to readers?

In addition, we discussed how we could ask follow-up questions to get even more detail and paint a fuller picture. Some of the prompts we used included “I heard you mention _____, can you tell me more about that? I heard you say _____, can you tell me more about why?” When interviewing people about their lives, it can sometimes take time to get some of the deeper answers we seek, so as part of our interview protocol, we also noted that we could ask interviewees to draw (or express through a medium most comfortable to them) their answers and then share their reflections. Another option was to ask the loved ones we interviewed if they might share pictures of themselves growing up and talk about what they remember from those moments.

Resistance 101

Once we had a complete interview protocol, we practiced interviewing skills by using the Resistance 101 mixer lesson on the Teaching for Change website. I added a few additional people to the lesson to feature Black women and girls, including Judith Jamison, Faith Ringgold, Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, and Claudette Colvin. I introduced the activity by noting, “This activity serves two purposes. One, we can use the mixer to highlight the stories we do not often learn about in history that emphasize the everyday courage and resistance of people around us. Two, it will give you an opportunity to practice interviewing techniques in preparation for collecting oral histories.”

We imagined ourselves in the lives of activists, organizers, and artists, and interviewed one another in breakout rooms using our collective interview protocol. This helped us to begin to feel comfortable with asking the questions on the sheet, as well as asking our own follow-up questions. The interview process was a delicate dance of being present with the other person to authentically listen to what they were saying and also make note of what they were not saying. The spaces between their reflections were areas for follow-up questions. Since the mixer bio sheets only have introductory information, the co-researchers did more research on follow-up questions they were not sure about. Co-researchers took copious notes about their interviewing partners’ answers and then came back to the full class to share the highlights.

Threads of Loved Ones’ Stories

Over the span of a week, we collected oral histories from at least one loved one. My prompt for them was “Take our collective interview protocol and use it like a script. Maybe you go through each question or select ones that are most relevant and speak to your heart. You can also add questions throughout the conversation. Think of it more like a conversation and let your curiosity guide you. When you interview your loved ones, you can ask for consent to record the conversations and/or you can take notes in your journals. Make note of any words or quotes from their stories that really move you.”

Camille and Olivia interviewed multiple loved ones to see how the stories intertwined. After everyone had the opportunity to collect at least one oral history, I asked, “What did you notice from the histories you collected? Was there a quote or something that your loved one shared that really stuck out to you? Why?”

Alia interviewed her grandmother, who she found out is a writer. Alia shared her grandmother’s statement: “I write because I know one day my story will need to be told.” Alia grew quiet, as she pursed her lips together in a slight smile, affirmatively nodding as others filled the chat box with their support. She went on to say that her grandmother experienced some challenges and struggles like not having equal or equitable access to education, yet continued to find a way to pursue an education to pave a way for her family. Her grandmother used her writing to catalogue some of her own story, which I could see spark a light in Alia, who used song lyrics to express her feelings. Her grandmother’s story was important because within it, it offered a glimpse into the everyday courage and persistence of Black communities. I shared with the group, “Alia, your grandmother’s story shows both collective struggle and creative expression.” We carried her grandmother’s declaration with us throughout the program because it served as a grounding reminder that our stories carry power and necessary truth within them.

After Alia shared, Mackenzie leaned into the Zoom screen to highlight how she interviewed her mom, who talked about how she was inspired by her own mother. Her mother witnessed Mackenzie’s grandmother work to care for and protect their family and community, despite experiencing discrimination. Olivia, a passionate dancer and poet, interviewed three of her friends, who all named their mothers as their inspiration. Some co-researchers discussed how their loved ones experienced racism and discrimination in the workplace or in their community, and others in school.

We typed our notes and transcripts from the oral histories into a separate collective Google document. After about 20 minutes, I prompted, “If you see a word, phrase, theme, or idea come up more than once, I invite you to highlight those.” Each co-researcher chose a different highlighter color and the document was filled with yellows, blues, pinks, and greens. I said, “The words, phrases, themes, and ideas we’ve come up with and highlighted — these are our codes. When we take codes directly from the words that were written, those are called in vivo codes. Now, which codes do you think really speak to the data, the notes you’ve written down? What themes do you notice in the data, in the experiences? What words, phrases, or ideas are coming up more than once?”

Briana, a creative entrepreneur, noted, “I’m noticing that racism came up in many of the stories.”

“What is similar in these experiences?” I asked.

“It wasn’t only individual acts of racism they experienced, but it was also from different institutions like school and the workplace. Also, many of the people we interviewed came from different places, so it was something much bigger than just individual acts of racism they were experiencing,” Briana said.

We began to weave the threads of the stories together to see how structural and systemic racism and oppression impacted their loved ones and their stories. We heard stories about loved ones not learning Black history in school, but learning it from their loved ones in their families and communities. There were stories about activism and resistance during the Civil Rights Movement, alongside stories of friends who used their phones to capture moments through photography during Black Lives Matter protests during summer 2020. Co-researchers noted the similarities by saying that they felt like they were still asking for the same rights as their loved ones. Lisa, a gifted instrumentalist, said, “In the way it’s written in textbooks it seems like this happened so long ago, but it wasn’t. It was not that long ago.” I affirmed her statement as she continued, “I also want to say I was thinking about something that I saw. It was a comment on a post on social media where someone was like ‘You can’t keep blaming what happened to your ancestors on us.’ The comment under it was ‘It wasn’t our ancestors. You mean our grandparents and our great-grandparents?’ That really made me think and collecting the oral histories reminded me of this.”

“Exactly,” I said. “One thing that I’m learning from this experience is that this history is still happening. When stories are shared that perpetuate this idea that this history was so long ago, it makes people believe that we are beyond the need to change things. It actually makes the status quo continue because it can make people feel complacent.”

The co-researchers wanted the narrative to reflect how present-day struggles were interconnected with the past. They were also clear that they did not want the stories they tell to focus only on oppression.

I asked, “What other words are coming up? What do you think that means about the stories we’ve collected?”

“Resistance is a word that’s highlighted many times,” shared Lisa. “We resist negative stories by sharing our art and our stories. Black history isn’t just full of suffering . . . they should explain a lot more of the successes that are in our history and that make us who we are . . . not everything is suffering for us. There’s joy, art, and love too!”

Jessie, an accomplished animator, added that all of the loved ones she interviewed also talked about “supporting our people.”

Whether through passing down knowledge, creating space for political education for their community inside and outside of the home, or providing care, many of the oral histories were about Black kinship and love. When some of the co-researchers asked loved ones “What made you march? What made you speak up?” a common answer was “Because we have to take care of each other.” Because of this, we ended each session by shouting “Peace and love!” into our screens.

The narratives we collected were about the kind of love that encourages us to feel empowered in our critiques of society. The stories were about love that roots us in affirming Black culture despite society’s attempts at co-opting and disparaging it. These stories, the stories of everyday love, don’t make it into textbooks.

“Stuff That’s of Importance”

I followed up the conversation with questions to further explore what the experience of collecting oral histories was like for co-researchers. “What was it like to collect your own data? What was it like to ask questions of someone and take down notes? What was that experience like for you?”

After a pause, Olivia chimed in. She giggled. “It was interesting . . . different. When I talk to my friends, we usually talk about surface-level stuff. But, with this . . . we talked about stuff that’s of importance.” Although some had interviewed mothers and grandmothers, others looked to friends and other members of their communities to learn more about their stories. For some, they felt that although it was uncomfortable at first, it deepened their relationships and allowed them to understand one another’s backgrounds and experiences.

I asked, “From the words and themes you highlighted, how might you express this through art? What story do you want to tell with your artwork? It can be anything you choose.” Although textbooks are often written documents, I encouraged students to think about the many ways stories can be shared so that readers, or audiences, not only see or hear the story, but feel the story.

The co-researchers in the program decided that for our community arts showcase they wanted the title to reflect the oral histories they collected by calling it #HistoryRewritten. Jessie created an animation that featured different moments in history. Some of the history we had discussed during the program, other moments she had learned at home from her loved ones. The animation moved through drawing after drawing of people such as Robert Smalls, who in the midst of the Civil War commandeered a Confederate ship to lead its Black passengers to freedom. The animation highlighted people like Florynce Kennedy, a Black feminist lawyer and organizer who countered racism in journalism, organized for abortion rights, and was a founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus. The faces of each figure had a solid block covering their eyes. Kendrick Lamar and SZA’s song “All the Stars” played in the background: “This may be the night that my dreams might let me know, all the stars are closer, all the stars are closer, all the stars are closer.” When Jessie presented her animation to the audience of invited loved ones, she followed up by explaining the artistic choice to conceal the faces: “What matters is that they helped change things and they could be any one of us.” She said it was the everyday acts of courage that influenced, shaped, and changed history.

There is a magic in remembering the rich legacies from which we come, and also in learning about the everyday people in our classroom communities who have poured love and wisdom into each young person we meet. When we begin to uncover the truths of history through the lens of those we love, we can be reminded of the power we hold in being a part of a long continuum of change.

***

Oral History Using How the Word Is Passed

In the epilogue of How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, Clint Smith details conversations he has with his grandfather and grandmother that he weaves into his telling of the history of enslavement. Smith states: “Still, each passing year I have become acutely aware that the past is not only housed in museums, memorials, monuments, and cemeteries, but lives in our lineage. I realized that, in an effort to dig into the archives that explain the history of this country, I had forgotten that the best primary sources are often sitting right next to us.”

Although we completed the oral history project in Black Girls S.O.A.R. before I read Clint Smith’s book, I saw a synergy between the oral histories we collected and Smith’s writing. Here I share some sparks for how to facilitate an oral history lesson using How the Word Is Passed as an anchor text, or central text around which a lesson is built. In the two project options for an oral history lesson that follow, young people use key excerpts from Smith’s book — “We Can Learn this History” (pp. 289–290), “Grandfather” (p. 273), and “Grandmother” (p. 279) — as inspiration to tell their and their loved ones’ stories.

Option 1

Build project parameters around Smith’s “We Can Learn this History” (see text on p. 27) to combat Eurocentric modes of knowledge production and encourage young people to embrace different ways of knowing, different sources of knowledge, and different kinds of remembering. Young people may create a spoken word poem, an animation, a collage, a song, motifs for dance choreography, or use another form of expression that best represents their answers to prompts such as “Who can we learn history from? Where does this history live? How can we explore this history?” Using the findings from the data they collect, they can reflect on the process of examining history through the experiences of their loved ones. Possible reflection prompts include “What was it like to learn history from your loved ones? What did you discover about yourself throughout the process? What about history may you see differently after collecting oral history testimonies?”

As another example, young people might use the line “We can learn this history from” to begin each line of a collective poem. Each young person could insert one line from what they discovered to end with a class poem that describes the varied ways they’ve learned history.

Option 2

Use Smith’s “Grandfather” and “Grandmother” texts (see p. 27) as inspiration for what young people might create based on their own loved ones’ histories. Young people could write about their experiences interviewing their loved ones, similar to Smith’s grandmother poem. Prompts could include “What did you notice and observe while you were interviewing your loved ones? What thoughts and feelings came up in the moment? What did you ask your loved ones? What do you still wonder?”

Another possibility could be to write about the year their loved one was born, similar to Smith’s grandfather poem. Educators might ask “What happened the year your loved one was born? Were there any significant events? What was the world like during that year?” Young people could collect artifacts their loved one may have from that year and identify other sources of information that can paint a fuller picture of what was happening the year their loved one was born.

—Cierra Kaler-Jones

***

We Can Learn This History

by Clint Smith

We can learn this history from the scholars who have unearthed generations of evidence of all that slavery was; from the voices of the enslaved in the stories and narratives they left behind; from the public historians who have committed themselves to giving society language to make sense of what’s in front of them; from the descendants of those who were held in chains and the stories that have been passed down through their families across time; from the museums that reject the temptation of mythology and that prioritize telling an honest and holistic story of how this country came to be; from the teachers who have pushed back against centuries of lies and who have created classrooms for their students where truth is centered; by standing on the land where it happened — by remembering that land, by marking that land, by not allowing what happened there to be forgotten; by listening to our own families, by sitting down and having conversations with our elders and getting insight into all that they’ve seen.

At some point it is no longer a question of whether we can learn this history but whether we have the collective will to reckon with it.

Grandfather

by Clint Smith

The year my grandfather was born, a gallon of gas was twenty cents and a loaf of bread was nine. Slavery had ended six decades ago, and twelve years later everyone would forget. The year my grandfather was born, he had eight siblings and two parents and a grandfather born into bondage he tried to bury. The year my grandfather was born, millions of Americans were unemployed and over a thousand banks shut down. The Great Depression had taken a deep breath, and the US didn’t exhale for years. The year my grandfather was born, twenty-one people were lynched and no one heard a sound. The trees died and the soil turned over and the leaves baptized all that was left behind. The year my grandfather was born, there were full trains leaving Mississippi, and only empty ones coming back.

Grandmother

by Clint Smith

The year my grandmother was born, the Florida Panhandle was burning hot with white terror. Black children were taught to keep their eyes down, their mouths shut, and to make it home before the sun dissolved behind the trees. The year my grandmother was born, the country was on the cusp of entering a war being fought across two oceans. Black men would be sent to fight for freedom and come back to a land where they didn’t have their own. The year my grandmother was born, she was held in her mother’s arms and had no way of knowing how soon that embrace would disappear and never return, how soon her mother’s face would become something she couldn’t remember. The year my grandmother was born, there were laws that wrapped themselves around the necks of everyone she knew, and no one knew if they would let go.

These excerpts from pages 289–290, 273, and 279 of How the Word Is Passed by Clint Smith are reprinted with permission of the publisher, Little, Brown and Company, for use with this lesson.